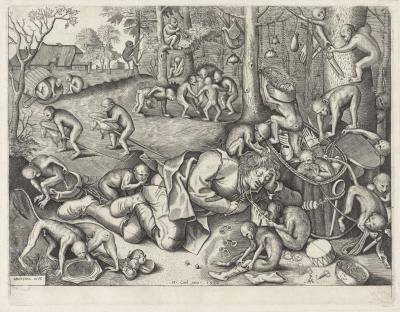

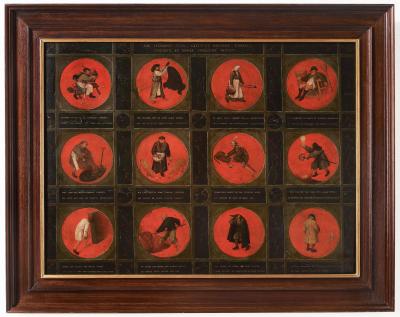

"The banderole at the top of the banner at left proclaims the setting for Bruegel’s scene of a church festival (kermis) as the village of Hoboken, a few miles south of the city of Antwerp. The banner’s motif of crossed arrows, in juxtaposition with the group of archers standing just below, identifies the kermis with the festival of the Longbowmen (Handboog schutters), held the day after Pentecost, typically in the month of May. (1) The shooting contest, depicted as improbably taking place in the middle of a crowded village square, was the centrepiece of the celebration. The elevated perspective and high horizon line allow the viewer to wander spectatorially though a variety of activities – a church procession, figures dancing in the round, crowds enjoying a play or local rhetorician (rederijker) performance, amorous couples embracing.

Festivals like the kermis were popular entertainments. As early as 1531 Charles V had tried to impose limits on their number and duration. Visitors from Antwerp descended on villages like Hoboken for rural entertainment, and wealthy merchants bought up country estates nearby. Ludovico Guicciardini, an Italian merchant famous for his description of the Low Countries, owner a home near Hoboken. (2) The publisher Tylman Susato included a festive dance from the village in one of his popular Dutch songbooks. (3) Contemporary inventories attest to the popularity of painted and printed scenes of the peasant kermis.

Scholars are divided on how the viewer was meant to interpret Bruegel’s picture of festivity. An engraving after the drawing, published by Batholomaeus de Mompere, is inscribed: “The peasants delight in such festivals: to dance, jump, and drink themselves as drunk as beasts. They insist on holding their kermises, even though they have to fast and die of the cold.” (4) This text paraphrases the inscription on another print of a peasant festival published by de Mompere, designed by Pieter van der Borcht. (5) Van der Borcht’s print clearly depicts those drinking to excess, brawling and vomiting, leading some to read Bruegel’s drawing as conveying a similar moralizing and satiric viewpoint. (6)

Yet while several couples embrace and a number of festival goers have lowered their trousers (most notably the squatting figure positioned for comic effect directly next to the archer’s target), Bruegel’s image is devoid of fighting and excessive drinking. The inscription on another kermis print designed by Bruegel, Kermis of Saint George, bears a more ambiguous inscription: “Let the peasants hold their kermis”. (7) Published around the same time as the Kermis at Hoboken by Bruegel’s usual publisher, Hieronymous Cock, the inscription on Kermis of Saint George signals the possibility of a more positive interpretation of the scene.

The year Bruegel drew Kermis at Hoboken, 1559, marked a change in Hoboken’s ownership: William of Orange sold the manor to Melchior Schetz, who passed the title to his brother Balthazar. The same year Philip II, ruler of the Low Countries, reissued his father’s decrees limiting festivals. Since Hoboken was known for celebrating three major feast-days, the inscription on Bruegel’s Kermis of Saint George has been seen as an appeal to the new lord of Hoboken to maintain the status quo despite the renewed limitations on feast days. (8) However, the precise relationship between Bruegel’s two designs is not clear – which print was designed first, why the artist published similar designs with two different publishers in a short space of time (Bruegel only worked with de Mompere in this single instance), and if the two prints were meant to be seen as a pair. (9) The compositional similarities between the two designs are striking, as both include games in the lower left corners, a strong diagonal with a wagon at the centre, and a fool with children in the foreground.

While visiting such feast days and buying images of peasant festivity were popular activities among the middle class, Bruegel includes no one with whom the viewer easily can identify. The figures positioned either side of the artist’s signature seem to indicate both a visual invitation and a warning. While the figure to the left faces the scene, his hand extending towards the artist’s name, the pair of figures to the right, one man seated next to a jug, the other man apparently admonishing him, offer a warning – a kermis may be diverting but should not tempt overenthusiastic participation.

Stephanie Porras

The Courtauld Gallery, London.

Credit Line: The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London.

Footnotes:

(1) Monballieu 1987, pp.193-94.

(2) Gibson 2006, p.82.

(3) See Porras 2011, pp.3-6; Riemsdijk 1888.

(4) Gibson has suggested the final word of this inscription (kauwen) could mean ‘chewing’, creating a more comic tone. See Gibson 2006, p. 81.

(5) New Hollstein 2004 (Mielke, vol. 12), no. 170; Raupp 1986, van der Borcht no. 4.

(6) For example, see Raup 1986, pp. 245-47; Sullivan 2010, pp. 56-58. Nadine Orenstein has suggested that the prints be viewed as a pair, with their difference in tone and style reflecting de Mompere’s ambition to appear to a wide market: see New York 2001, p.198. At the time of the print’s publication, de Mompere was the manager of Antwerp’s Schilderspand (dedicated art market) and must have been savvy about consumer demand. See Vermeylen 2003, pp. 54-61.

(7) New York 2001, no. 79; New Hollstein 2006 (Orenstein, vol. 15), no. 42.

(8) Monballieu 1974; Monballieu 1987.

(9) Orenstein (in New York 2001) has suggested that the current sheet postdates Kermis of Saint George, as Bruegel would have first worked with his regular publisher, Cock, before turning to his rival de Mompere."

This text comes from 'Master drawings from The Courtauld Gallery', ed. by Colin B. Bailey and Stephanie Buck, London 2012.