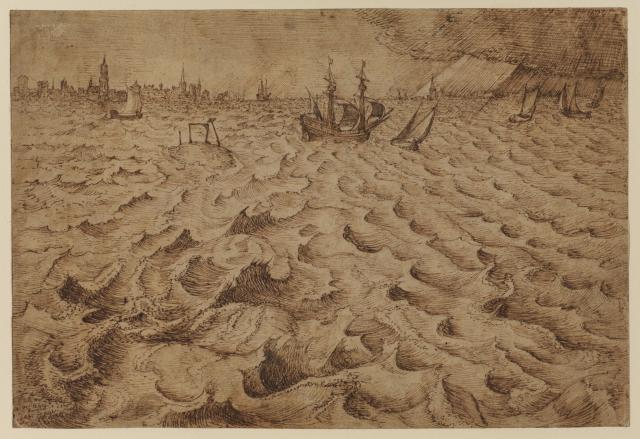

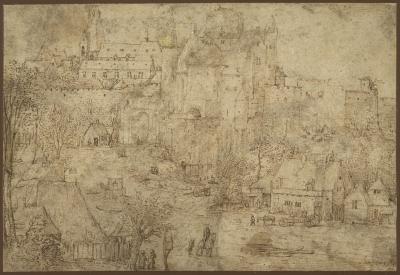

This exquisite and understudied drawing of a stormy marine view is unique in Bruegel’s oeuvre. Nearly two-thirds of the sheet is devoted to the study of rows of waves receding into the background. Leonardo da Vinci’s water studies from the early sixteenth century are the only precedents for such a vivid transcription of wave motion.

While most scholars have connected Bruegel’s treatment of the waves here to those in the design for the engraving Spes, signed and dated 1559, Manfred Sellink has recently compared the Courtauld sheet to Bruegel’s designs for sailing vessels etched and engraved by Frans Huys from 1561-65. (1) The plastic modelling of the undulating waves in the drawing is similar to that in these later prints, in both Bruegel used a graphic system of short strokes – dashes, hooks, dots and squiggles – to depict the water’s surface. In contrast, at upper right he used long, straight lines of varying density to convey the drama of a strong downpour punctured by a shaft of sunlight.

The limited scholarship on the drawing has focused on the juxtaposition at upper left of the small island with gallows and a city skyline reminiscent of sixteenth-century Antwerp. The large tower at the centre is similar in outline and relative scale to the city’s Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk. However, the scale of the river and the silhouette of other spires at upper right seem antithetical to this identification, leading some to conclude the scene depicts a generic or unknown view. The difficulty in reading the drawing’s topographic accuracy may be due to the traditional understanding of the sheet’s viewpoint as being across a river. If, however, we think of the view as being onboard a vessel heading upriver, approaching the port of Antwerp from the North Sea, these topographical inconsistencies are resolved.

If Bruegel meant to depict Antwerp, the gallows island in the middle of the river is certainly the work of fantasy. According to several mid-century maps of the city, including one published by Hieronymous Cock in 1557 (fig. 39), the wheel and gallows were placed outside the city walls across the river. (2) Thus Bruegel’s artistic invention may have had particular local resonance, as the riverside was the site for executions. The island, with its symbols of death and municipal justice, is tiny among the waves, underscoring man’s fragile hold on life and fortune. This was a timely message, as there were a number of prominent deaths in the years around 1559 (including those of Charles V, former ruler of the Low Countries; Queen Mary of England; Christian II and III of Denmark; and Pope Paul IV).

The depiction of a stormy sea would also have had particular poignancy for the inhabitants of Antwerp, one of the North Sea’s premier merchant ports. Bruegel’s fellow Antwerp residents would recognise the large three-masted ship at upper centre heading towards the squall as a reminder of the dangers of the sea trade. Lodovido Guicciardini, describing Antwerp in 1567, wrote: “At one glance one can take in a great sweep of river with the perpetual ebb and flow of the sea… observe so many different kinds of ships… so that every hour there is something new”. (3) Reflecting the importance of the marine economy to the city, Bruegel probably began his numerous designs for ship engravings around the time of this sheet’s execution. (4)

The drawing’s most striking feature, however, is the waves themselves. The water’s visual dominance underscores the power of the natural world, dwarfing the architecture of the skyline and the modern technical prowess of the sailing vessels. Pushed to the top third of the sheet, man’s place in the world is rendered as limited. Hans Mielke suggested that the drawing was an allegory of man’s struggle against the dangers of the world; more recently, Manfred Sellink posited reading the gallows as a symbol of transgression and the strong beam of light at upper right as a sign of hope. (5)

Yet the composition of the sheet with its high horizon also directly parallels the elevated viewpoints of Bruegel’s earlier series of prints, the Large Landscapes. (6) The sense of physical distance in these designs has been compellingly related to the contemporary interest among Antwerp humanists in neo-Stoic philosophy. (7) The early modern Christian neo-Stoic sought to detach himself from the world, not in the model of an ascetic, but to gain philosophical perspective on his surroundings.

A Latin proverb, published in emblem form in Jacob Cats’s 1627 Sinne- en mine-beelden but probably known earlier, encapsulates this stoic perspective: “Tangor, non frangor, ab undis” (I am touched but not broken by the waves). From 1559 onwards, there was an atmosphere of increasing religious and political tension in the Low Countries, as Philip II imposed a new system of bishoprics alongside tougher heresy laws, upsetting the local nobility and those sympathetic to the new Reformist religion. The appeal of neo-stoic detachment, therefore, was not just a philosophical fashion but an increasingly useful tactic for negotiating the fractious politics of the region.

In such an environment, Bruegel’s drawing could have functioned as an autonomous work, intended to generate discussion among erudite collectors who appreciated both the artist’s skill and the network of potential interpretations and references (historic, literary, contemporary) the sheet generated. – Stephanie Porras

The Courtauld Gallery, London.

Credit Line: The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London.

Footnotes:

(1) Sellink 2013, pp. 308-9.

(2) New Hollstein 2006 (Orenstein, vol. 15), no. 4.

(3) Guicciardini 1567, p.107.

(4) New York 2001, nos. 89-94; New Hollstein 2006 (Orenstein, vol. 15), nos. 62-71.

(5) Mielke 1996, p.61; Sellink 2007, p.133.

(6) New York 2001, nos. 24-35; New Hollstein 2006 (Orenstein, vol. 15), nos. 49-60.

(7) Müller-Hofstede 1979; Koerner 2004, pp.221-22.

This text comes from 'Master drawings from The Courtauld Gallery', ed. by Colin B. Bailey and Stephanie Buck, London 2012.